CANNING STOCK ROUTE - Some Background Notes

Laurie McLean

Preface

During various periods of field duty with NatMap between 1969 and 1977, I spent some 330 days (about 11 months) in total under fairly basic camping conditions both supporting and undertaking mapping surveys in the Great Victoria, Gibson, Little Sandy and Great Sandy Desert regions of Western Australia. On numerous occasions I crossed over parts of the Canning Stock Route (both on the ground and in the air) and also obtained water for survey party use; mainly from Well 33 and also Well 35 (but only in 1969). Thirty years after last working in the area, I made a recreational vehicle trip along the stock route in 2007 to fill in the big bits I had previously missed and to become reacquainted with the area's uniqueness and beauty. Another NatMapper, Lawrie O'Connor accompanied me on that trip. Following the circulation to families and friends of travel notes and images taken during the trip, we received queries from people wanting to know more about both Canning and the route. This paper seeks to address such queries. However, the reader is warned that this is not an academic or definitive work. Rather, it is something I could put together conveniently for personal use to meet the above aim. Convenience was a key driver in that I had all cited references on hand or could access them from the internet. While I have drawn extensively from this reference material, I am conscious that other significant works, for example Ronele and Eric Gard's Canning Stock Route: A Travellers Guide have not been consulted; due to a mix of access difficulties and indolence. I have sought to resolve conflicts between references such as with dates by giving weight to the greatest detail (eg July 1959 is used from one source rather 1958 from another). In other cases I have simply relied on personal preference to resolve such matters. I trust the reader can gain some useful and interesting background from the following. As always responsibility for any errors or other shortcomings rests with the author.

What, Where, Why, When?

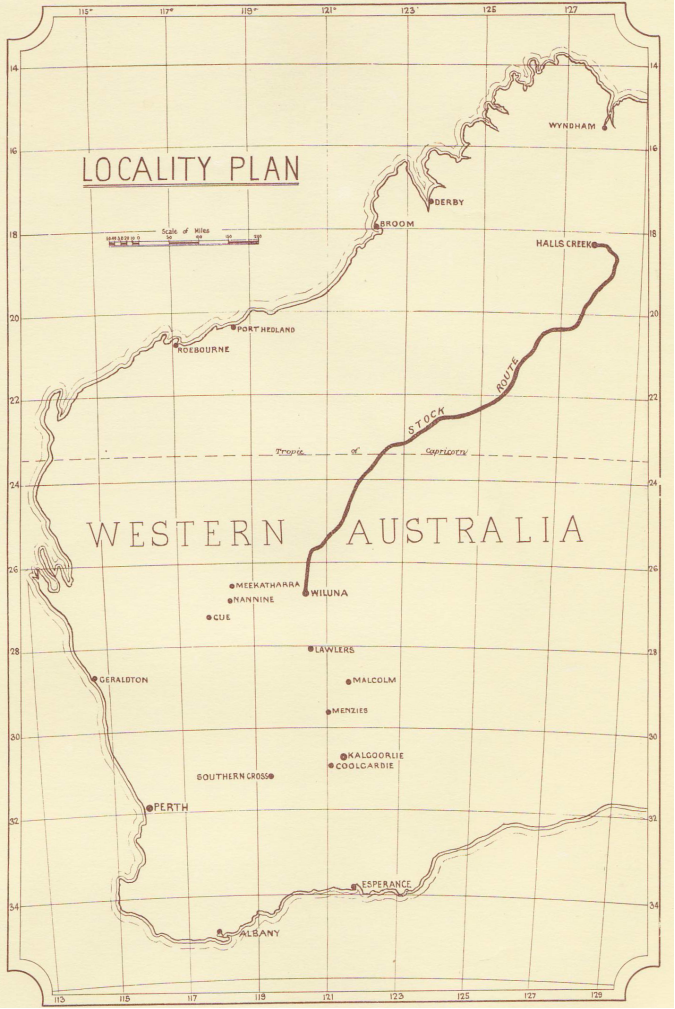

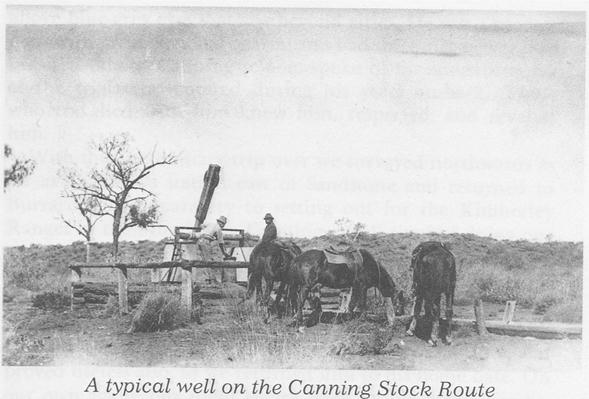

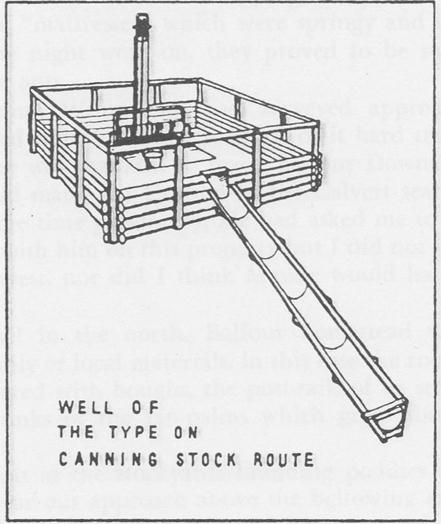

The Canning Stock Route is said to be one of the most isolated tracks on earth. It covers a distance of about 1,800 km across Western Australia's semi arid and desert country from Wiluna (in the Eastern Goldfields about 700 km north east of Perth) to Halls Creek in the East Kimberley (about 350 km south of the port of Wyndham and about 130 km west of the Northern Territory border), see Appendix A. It was constructed as the Wiluna - Kimberley Stock Route during 1908-10 by a party of 26 men under Surveyor AW Canning. (The route was formally renamed the Canning Stock Route in February 1967 but had previously been referred to by that name for many years.) During 1906-07, Canning had led a smaller exploration party to establish the feasibility of such a route. According to Canning's field notes, the original stock route had 68 native waters, bores and wells; these are listed in Appendix B and a typical well is depicted at Appendix C. Over time more wells were built and today the usual tourist route sees Well 51 Weriaddo (the northern most-well on Lake Gregory Aboriginal Land) as last of the Stock Route.

Cattle tick Boophilus micropolus (Canestrini) was introduced into Australia with the importation of cattle from what is now Indonesia in the early 1800s. It spread through the tropical north with devastating results on infected cattle that developed the fatal red water fever. Cattle in the West Kimberley and Pilbara were not affected and landholders in these areas objected to infected East Kimberley cattle being overlanded through their country. Shipping cattle to southern markets from Wyndham was uneconomic so East Kimberley pastoralists began lobbying the state government for development of a stock route through the desert from Sturt Creek to Wiluna so they could supply the Eastern Goldfields. The pastoralists argued (correctly as it turned out) that cattle tick would not survive in the dry desert environment and so there would be no need to have the cattle dipped (for tick control) before droving them south.

Wiluna

Wiluna is a small regional service centre for the surrounding pastoral country and mining operations. Prospectors Woodley, Wotten and Lennon discovered gold near Wiluna on 17 March 1896. Originally called Weeloona, the spelling was changed when the town was gazetted in 1897. Origin of the name is uncertain but is thought to be a native word for place of the wind or for the call of the stone curlew, a local native bird. Gold mining saw the town's population peak at around 9,000 people in the mid 1930s. At this time there was a regular train service to Perth, an air service, 4 hotels and numerous other facilities. World War 2 had a severe impact on gold mining and the town declined, particularly when underground mining ceased. By 1953, the population was 350 people and by 1963 it was only 90 people. More recently the population has stabilised at about 300 which includes a high proportion of Aboriginal people.

Halls Creek

Today, Halls Creek is a thriving regional and tourist service centre on the Great Northern Highway (National Route 1) with a population of about 1,300 people including a high proportion of Aboriginal people. It is named after prospector Charlie Hall who with Jack Slattery made the first discovery of gold in Western Australia in 1885. (This discovery was near the old townsite about 15 km east of the town's present location.) A short but intense gold rush followed Hall and Slattery's discovery and a town quickly grew to 2,000 people. However, gold finds soon dwindled and after the discovery of gold at Southern Cross in 1888, Halls Creek was pretty much a ghost town. Interesting remains of the old town still exist but with the building of an airfield and subsequent re-routing of the highway, the town was progressively shifted to its present site between 1948 and 1954.

Use of the Stock Route

There were some 35 cattle drives down the Canning; of which 29 were of Billiluna cattle. The first cattle to head down the stock route was a mob of 150 bullocks that left Flora Valley Station (south of Halls Creek) under drover James Campbell Thomson (aged 38) with Christopher Frederick George Shoesmith (aged 32) and a part Aboriginal named Chinaman (aged 25 years). (The party had included Fred Terone but he returned to Halls Creek after a few weeks due to conjunctivitis.) Tragically the other 3 were speared to death by natives on the night of 25-26 April 1911 at Well 37. The tragedy was discovered by drover Tom Cole (of Wyndham) who was bringing down the next mob. Cole found Thomson's horse partly eaten at Well 45 and by the time he reached Well 38 the number of wandering cattle alerted him that something was amiss. Cole camped his cattle and rode ahead to discover the bodies on 30 June 1911.

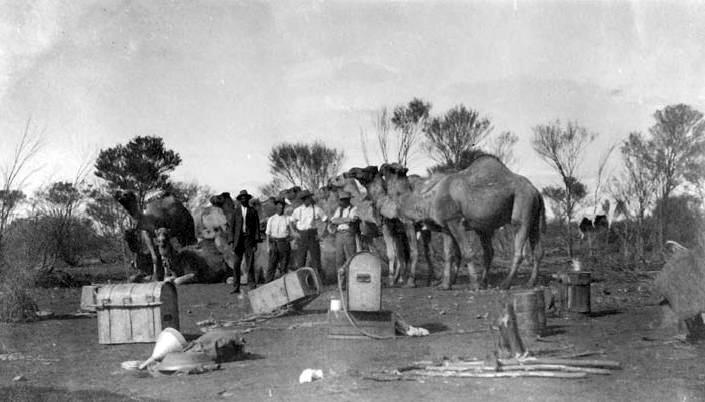

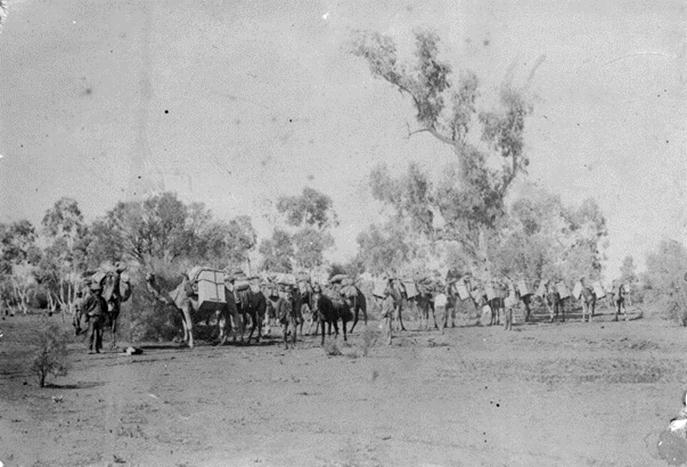

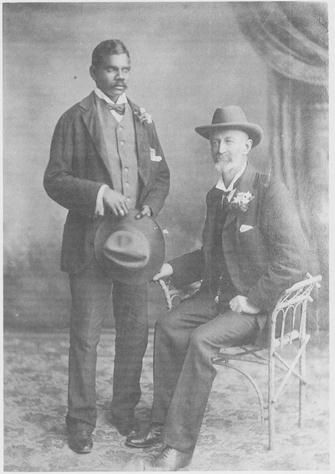

For some years after Tom Cole's trip the stock route was not used, apparently because of its remoteness and fear of native hostility. The next party known to traverse the route was magnetician Edward Kidson (1882-1939, an English born New Zealander) who left Leonora (300 km south of Wiluna) on 20 May 1914 and arrived at Flora Valley Station on 16 August. As the chief observer in Australia for the Carnegie Institution of Washington Department of Terrestrial Magnetism (CIW/DTM), that was undertaking a world wide magnetic survey project, Kidson made observations for magnetic inclination, declination and horizontal intensity at 48 accurately positioned sites between Leonora and Wyndham. Kidson was accompanied by Messrs Clark, Cronin and Ryan as well as Nipper an exceptional Aboriginal tracker who had already made 3 journeys along the stock route with Canning. They used 12 camels.

At Wiluna, Kidson was advised to be careful of desert Aborigines which were said to be treacherous and unreliable. A number of times he warned off small groups of Aborigines that were following his party. At Well 36 he made a protective shelter with his stores and equipment and kept the camels tied rather than hobbled. His dog Nellie growled throughout the night for unknown reason. After reaching Halls Creek, Kidson travelled on to Wyndham and left there by sea. His party returned along the stock route; arriving back at Leonora on 23 November 1914. (See Appendix D for images of this expedition.)

In 1922, the Locke Oil Expedition travelled the Stock Route from Leonora to Halls Creek; it was led by geologist LA Jones and included as his assistant Horace Patrick Buckley (then a university student). The party comprised 11 men with a number of camels, see Appendix E. One of the expedition's camel drivers JV (Jock) McLernon was killed by a native nulla-nulla as he slept about 30 miles east of Well 37. Two other expeditioners fought off the natives and brought McLernon's body to the well for burial. (In 2007, the old metal plaque on this grave was marked W McLennon, apparently in error.)

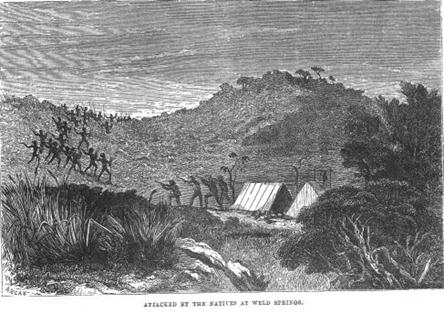

Tom Cole had criticised the stock route for stages being too long and feed being poor. He said an advance party had to travel ahead in case 2 successive wells were unfit for use and the wells provided sufficient water only for mobs of 300 cattle with a week being needed for wells to replenish. William Snell a land owner and well known bushman said the route should be positioned 100 km further east where there was more feed. Following pressure from station owners, the government agreed to re-equip the stock route in 1928. It initially gave the job to Snell who commenced from a base at Weld Springs in February 1929 and by October his party was at Well 35, having made 5 new wells and reconditioned 33 others. With the northern wet season approaching and steel supplies exhausted, Snell decided to return to Wiluna where he sadly found his only son had died on 15 September. It was perhaps due to Snell's personal situation, that the government asked Canning to come out of retirement to complete the task, which he did between March 1930 and August 1931.

During the 1930s, use of the stock route increased and for the next 20 years at least one mob a year was brought down. George Lanagan of Billiluna made four trips down the stock route, his last full trip being in 1940. On this last trip, Eileen Lanagan (George's wife) became the only known white woman to come down the route with a mob of cattle. Each day she would ride ahead of the cattle and prepare the team's camp and burn any poison bush (Gastrolobium grandiflorum) before the cattle could graze on it. (On 7 March 1940, Lanagan marked the graves at Well 37.) Jerry Pedro a part Aboriginal who retired near Broome, travelled down 3 times with Wally Dowling and Mal Brown (Mal made a total 11 trips up or down the route). Jerry and Wally also took up a mob of horses they trapped east of Laverton. Jerry said progress on the track depended on the season. After a good wet there would be plenty of feed and water in the claypans; his last trip took 14 weeks. Between 1942 and 1944, fears of a Japanese invasion led to the stock route being prepared for the possible mass exodus of people and livestock from the Kimberley. The Kalgoorlie Water Supply reconditioned a number of the wells. In 1955, drover Jack Gordon brought down a mob of 500 cattle but lost many due to problems with drawing water at Well 20. As time progressed, drovers adopted new methods to make working the stock route easier. In latter years, portable petrol powered pumps and rubber hoses were used to draw water from the wells rather than the camel, whip pole and steel bucket. Towards the end of droving, the stock route could only be used by Billiluna Station due to concern of spreading pleuro-pneumonia to southern cattle. The last mob brought down the stock route left Billiluna in 1959 under Len Brown. He brought the mob to Well 22 where George Lanagan (then living at Meekatharra) took over to bring the mob to Wiluna, in July 1959.

Vehicles and others on the Stock Route

The source literature gives some slightly conflicting accounts on the history of droving and vehicle travel on the stock route. However, it appears that one of the first vehicle expeditions was that of Michael Terry. He completed a number of remarkable journeys in various parts of Australia in the 1920s and 30s. In 1925 his expedition travelled from Billiluna to the Southesk Tablelands (that are between Wells 47 and 48). In the 1930s, George Herbert from Wiluna drove as far as Well 10 and soon after surveyor H Payne also travelled on some of the southern section. In 1942, a convoy of 5 army vehicles under Captain E Russell attempted to travel the whole route from Wiluna. However, owing to a very wet season and boggy conditions near Lake White they had to turn back when about 16 km north of Well 11. Also in 1942, the Kalgoorlie Water Supply got a truck as far north as No 17 Water Killagurra when reconditioning wells. In 1954, George Lanagan led a party of 3 four wheel drive vehicles from Wiluna over station tracks to Talawanna homestead and then overland across the desert to Well 22.

In June 1959, Division of National Mapping supervising surveyor HA (Bill) Johnson did a geodetic traverse reconnaissance in a Landrover from Wiluna to Well 14. Johnson said this was to prove if the stock route could be traversed without the use of camels or packhorses and had followed his discussion with George Lanagan who believed it was possible to travel the whole stock route in a carefully driven normal four wheel drive. Starting in September 1962, Johnson travelled the stock route alone in an AB120 International from Well 35 to Billiluna and then on to Halls Creek; a vehicle distance of 782 km. During this trip, sites for 23 survey stations were selected to give line of site for the survey traverse between Well 35 and Halls Creek. These survey stations were established and observed during May - August 1964; commencing at Halls Creek. The 1964 traverse party was led by NatMap's RA (Reg) Ford, senior technical officer.

To assist with access for the vehicles of his 12 man party, Ford arranged for a contractor to grade a track generally near the stock route between (then) old Billiluna homestead and Well 45; a distance of about 250 km. After Well 45, Ford continued scraping an access track using his party's 2 Bombardier light tracked vehicles powered by 6 cylinder Chrysler engines. However, the Bombardiers proved unsuitable in the sandhills and the engines eventually failed near Well 41 after a further 140 km of track were made (but still about 180 km north of the Well 35 objective). As the track Fords' party made was to meet the access needs of the survey, it didn't stick strictly to Canning's route. The Woomera rocket range and NatMap's survey needs resulted in several tracks being made across the stock route in the early 1960s. Many tracks were made in the western deserts by the Weapons Research Establishment's Len Beadell. Some were solely for NatMap's geodetic survey requirements. Beadell's track into Well 35 from the east followed the 1961 wheel tracks of NatMap's surveyor OJ Bobroff from Jupiter Well and Beadell's track from Well 35 to the Calawa Creek telegraph line near the west coast followed Reg Ford's 1962 wheel tracks as well as some 200 km of track Ford's party scraped with rudimentary equipment on the western end of this line. Two of Beadell's other tracks followed routes selected and plotted by NatMap, namely: the Young Range to Well 35 track and Windy Corner to Talawanna homestead track (which crossed the stock route near Wells 23 and 24). NatMap's survey parties visited and sometimes drew water from Canning wells during the late 1960s to mid 1970s including Wells 33 and 35 in 1969, Well 24 in 1970, Wells 24 and 33 in 1972 and Well 33 in 1975 and 1977.

According to a plaque at the site, on 21 November 1965, oil explorer and producer Western Australian Petroleum Pty Ltd spudded their Kidson No 1 well in the Canning Basin about 50 km south east of Canning's Well 33. The WAPET well was abandoned on 20 July 1966 at a depth of 14,539 feet (4,431 m). This oil search well was a significant undertaking and included the construction of a major access road for the heavy drilling and ancillary equipment. Referred to variously as the WAPET Sahara track, the WAPET road or the Kidson track, the road covered a distance of about 660 km. It ran from near the Wallal Downs homestead turnoff on the Great Northern Highway to Swindell's Field airstrip (about 340 km south east of the Wallal Downs turnoff). It then ran about 300 km further to the Kidson drill site and beyond for about 20 km to an associated airstrip and its termination at Beadell's Young Range to Well 35 access track (later referred to as the Gary Highway). Unlike Beadell's graded scrapes, the WAPET access was a made road with long sandy flats gravelled over and the (relatively few) sandhills it crossed cut into, clayed, gravelled and side fenced to limit sand drift. However, like Beadell's tracks, being unmaintained, it suffered the wash away and gutter forming ravages of the wet seasons and the corrugating effects of vehicle use as time progressed. As well as WAPET, this road was used extensively by NatMap (during the late 1960s and 1970s) and by numerous other travellers.

In 1964, Swindell's Field was used as a supply depot and base for native patrol officers involved in the clear out of the Martu people from part of their traditional lands affected by a 160 by 145 km dump area in which Blue Streak (or other) rockets from the Woomera range were intended to land. (In July 1965, NatMap's technical assistant, Bob Goldsworthy together with field assistants K Snell and W Sutherland recovered over 60 pieces of a rocket that came down to the north west of Well 35; the largest piece was 17' by 2'.) In a November 1964 report on a Blue Streak clear out patrol between Wells 30 and 40, native patrol officer Robert Macauley noted: The wells on the Canning are generally in good condition with the quality of the water good and safe without boiling. Supply was plentiful in all cases. The timbering at most wells has lasted surprisingly although there are signs of decay appearing. Most wells still retained buckets and windlasses, and in some cases, covers over the wells. Troughs are scattered around each well, and at Well 31 had been used as a wind-break by Aborigines in earlier days. The stock route is not readily visible from the air or even the ground at first. There are no cattle or human tracks visible. However, the Canning Basin itself becomes apparent on close scrutiny. For most of its course between Wells 30 and 40, it is marked by a conspicuous belt of numerous closely jumbled sandhills on its western side, an open spinifex plain about two miles wide to the eastern side, and a continuous eroded gravelly plateau with jutting low headlands about three miles to the east. The stock route follows the main basin which is a slight depression with a good coverage of low acacias. Wells 31, 32 and 33 are found among tea-trees, but Wells 34 - 40 are among the sandhills just to the west of the actual basin.

On 10 July 1968, Dave Chudleigh (a surveyor with the Australian Survey Office, Canberra) together with Rus Wenholz (from Queanbeyan) and Noel Kealley (from Perth) drove the whole length of the stock route. Travelling in 2 short wheelbase Landrovers on a private excursion during annual leave, this party faithfully followed Canning's route and reached Halls Creek 34 days later having travelled 2,575 km. They had fuel supplies positioned at Wells 35 and 48 and had a food resupply at Well 33. Theirs' was the first recorded vehicle traverse of the stock route.

During and since the 1970s, the stock route has seen increasing recreational use by private users and commercial operators in four wheel drive vehicles. Four wheel drive clubs, similar voluntary organisations and groups of interested individuals have done much to provide for travellers by improving and marking the track and reconditioning some of the wells. Chemical toilet facilities have been provided at Well 6 and Durba Springs, two of the most heavily used camping areas. Fuel and food supplies can be obtained from the Kunawarritji Aboriginal Community that has established extensive facilities near Well 33. (The settlement at Kunawarritji dates from the 1980s when members of the Martu people formed several outstation settlements in the western desert to protect their homelands and way of life after being encouraged, or perhaps more correctly, cleared out, as were other desert Aboriginal people in to missions on the edges of the desert in the 1950s and 60s when their lands were used for the rocket range.) Also, arrangements can be made with the Capricorn Roadhouse (on the Great Northern Highway south of the mining town of Newman) for fuel to be dumped at Well 23. Following an unsuccessful attempt in 1974, Murray Rankin and Rex Shaw walked the stock route from Wiluna to Billiluna in 1976. In 1991, Georgia Bore was established between Wells 22 and 23 by CRA Exploration Pty Limited providing good water for benefit of travellers. In 2007, Heidi Douglas travelled down the stock route with 2 camels and a horse. In July 2004, a solo transcontinental camel expedition camped at Well 49. Tourist use of the stock route is now so extensive that it is putting some pressure on this fragile country; just one example being absence of dead timber at the most convenient or picturesque camping sites due to camp fire use.

European Exploration

Between Wells 15 and 40, the stock route runs through traditional Martu lands. The nomadic Martu Aboriginal people are believed to have occupied the western desert region for around 26,000 years and few had contact with Europeans until the twentieth century. In the early 1960s, one tribal group in the McKay Range area (west of Well 23) had its first direct European contact when Len Beadell was surveying for the Talawanna track. For others, the clear out era saw their first contacts. In 1977, an old nomadic couple, Warri and Yatunga, were found living traditionally outside present day Martu lands about 150 km south-east of Lake Disappointment.

Apart from Canning, a number of European explorers travelled on, near, or across parts of the stock route. The first was August Charles Gregory who left Brisbane by ship in 1855, travelled up the Victoria River and established a depot at Timber Creek, now in the Northern Territory. From there he explored south in to the Tanami Desert and then to the west where in February 1856 he discovered and named Sturt Creek which he followed for some 300 miles until it ran into a dry salt lake (later known as Gregory's Salt Sea but is now known as Lake Gregory). Perceiving he had entered what he termed the Great Australian Desert, on 9 March 1856 Gregory turned north east to retreat to the Victoria River and later travelled overland to the Queensland coast. (Canning's Well 51 Weriaddo lies on the south western corner of Lake Gregory and his original stock route followed Sturt Creek much of the way from there to old Halls Creek. With its old homestead situated on Sturt Creek at the northern end of Lake Gregory, Billiluna Station of some 160,000 hectares was first taken up by Joseph Condren in 1920. In early September 1922, Condren and the station's cook Timothy O'Sullivan were shot dead by an Aboriginal known as Banjo.)

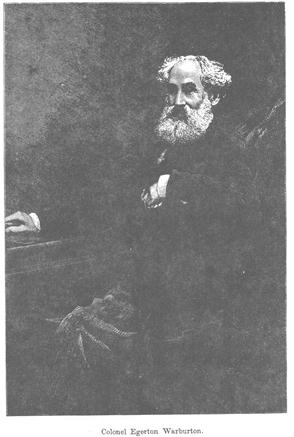

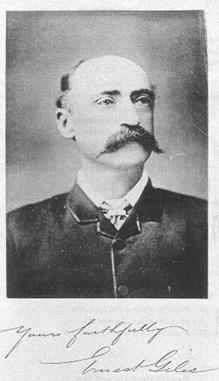

Peter Egerton Warburton's party crossed the northern part of the stock route in 1873 at Mount Romilly and passed near Well 47 on his way from the Overland Telegraph line at Alice Springs enroute to Joanna Spring then to the Oakover River and eventually Roebourne. In 1874, John Forrest in company with his brother, Alexander and others, succeeded in finding an overland route from Perth to South Australia, completing the journey in five months. He found and named waters on the southern section of the stock route that Canning later used namely: Windich Springs (No 4A Water), Pierre Spring (Well 6) and Weld Springs (Well 9). Between 1872 and 1876 Ernest Giles led 5 expeditions into Australia's unknown western interior, the last 2 on camels. On his final crossing from the Murchison River to the Overland Telegraph line in 1876, his party crossed the stock route between the Calvert Range and Trainor Hills to the north of Well 15.

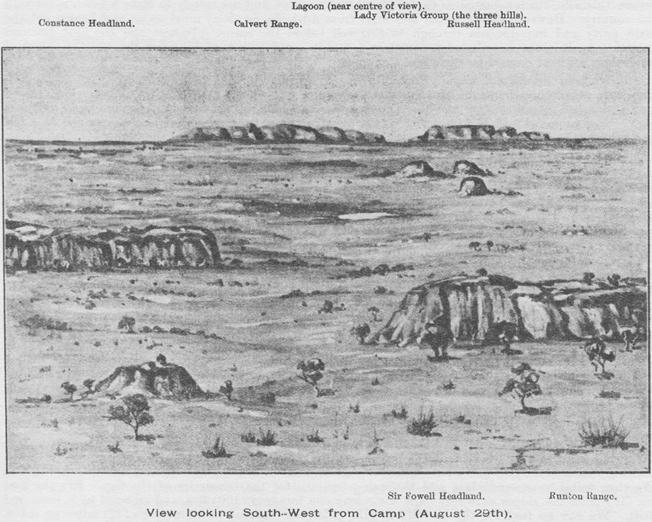

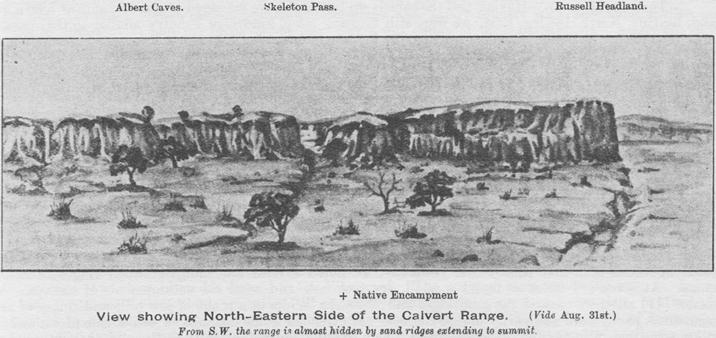

As leader of the so called Calvert Scientific Exploring Expedition during 1896-97, Lawrence Wells travelled to the east of the stock route with a reconnaissance party in 1896 naming, amongst other features, the Runton Range, Calvert Range and Trainor Hills (near Wells 15 and 16) and several weeks later with his main party he crossed the stock route between Wells 29 and 30, naming Thring Rock, King Hill and Lake Auld. Soon after his cousin Charles Wells with George Jones left the main party for further reconnaissance and perished when they were unable to find water.

The Hon David Carnegie's expedition from the southern goldfields to Halls Creek in 1896 touched on the northern part of the stock route around Wells 48 and 49; he named many features including the Southesk Tablelands, Godfrey's Tank, Breaden Pool, Twin Heads and Mount Ernest. Frank Hann, an outstanding explorer and bushman who endured indifferent luck and tough times through much of his life, discovered and named Lake Disappointment and the Mackay and McFadden Ranges during his exploration of the Pilbara east of Nullagine in 1897; his route came near Wells 19 and 20.

Readers interested in gaining further knowledge of these explorers can read extracts from their journals at Appendix F.

Canning - the Man

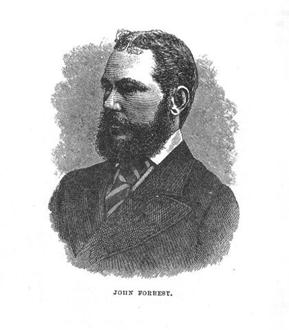

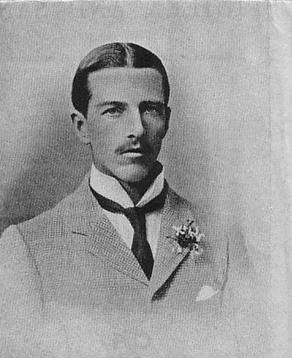

(Alfred Wernam Canning : Courtesy Eastern Goldfields Historical Society)

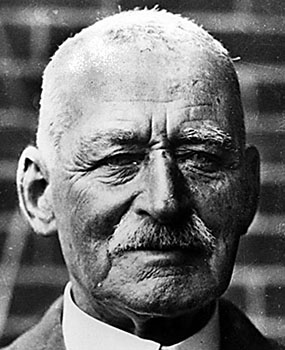

Alfred Wernam Canning was born on 21 February 1860 at Campbellfield Victoria, son of William Canning, farmer and his wife Lucy (née Mason). Educated at Carlton College Melbourne, he entered the survey branch of the New South Wales Lands Department as a cadet. In January 1882 he was appointed licensed surveyor under the Real Property Act. He served at Bega (1883-86), Cooma (1887-89) and as a mining surveyor at Bathurst (1890-92). On 17 April 1884, he married Edith Maude Butcher in the Mary Immaculate Roman Catholic Church at Waverley, Sydney. They had one son who died in 1923.

Canning joined the Western Australian Lands Department in 1893. In routine surveying over the next 8 years, he proved himself a first-class bushman and reliable surveyor, including leading a survey along the coast from Albany to Eucla. About the turn of the century rabbits were invading Western Australia from the east. Following a Royal Commission, in 1901 Canning was instructed to survey a route for a rabbit-proof fence. This took him from Starvation Boat Harbour about 125 km west of Esperance on the south coast to Cape Keraudren, 130 km north east of Port Hedland, over 1,800 km. Said at the time to be the longest single survey in the world, it took him three years to complete. Construction of No 1 Rabbit Proof Fence along his line was completed in 1907. Two other shorter fences were subsequently constructed and parts of the original and later fences are still maintained today. During this survey, owing to the loss of 2 of his camels, Canning walked 210 miles in 5 days, including one waterless stretch of 80 miles.

In 1906, the State government planned a stock route to bring cattle from the East Kimberley to feed the Eastern Goldfields. David Carnegie had explored further east in 1897 and concluded it was absolutely impracticable. Canning proved otherwise. With 8 men, 23 camels and 2 horses, he left Day Dawn (near Cue about 550 km north east of Perth) in May 1906, aiming to find water sufficient for stock every 24 km of the 1,800 km route. He reached Halls Creek in October 1906 with the task successfully accomplished. In January 1907, after resting and re-equipping, the party returned to Perth via the same route. Tragically, about 5:30pm on 6 April 1907 near what is now Well 40 one member of his party, Michael Tobin, was fatally speared by a hostile native. After his return, Canning faced publication of charges by E Blake, the expedition cook, that Aboriginals had been ill treated. A royal commission exonerated Canning in January 1908 although he had admitted chaining Aboriginals at night albeit with prior permission of the Commissioner of Police. Blake made his accusations (which he later withdrew) only after being informed he was not selected for Canning's second expedition.

Canning's optimistic survey and feasibility report to the government was accepted and he organized a second, larger expedition (of 26 men, 62 camels, 2 horses, 2 waggons, over 100 tons of equipment and 400 goats for milk and meat) to construct the necessary wells along the route. In temperatures varying from below freezing at night to extreme heat during the day, Canning led his party with mild courtesy and resolute example. Calculating distances principally by his own unvarying pace, he would walk for hours, regardless of the weather. Much of the country included desert sand-ridges 15-18m high which had to be crossed every km or so. Leaving completion of some of the southern wells for the return journey, he finished this Herculean task in Wiluna in March 1910. His telegram advising of this considerable feat was typically understated: Work Completed Canning. He addressed the Royal Geographical Society in London later that year on the benefits ...of the new highway and waterway between northern and southern Australia ...we have made (reported in the London Daily Express) and on the agricultural and pastoral potential of the north of Western Australia.

In July 1912, Canning became district surveyor for Perth. In 1915, he was a member of the Pastoral Appraisement Board. During 1917-22 he was surveyor for the northern district. He resigned from public service in 1923 and went into partnership with HS King as a contracting surveyor. In 1930, at the invitation of the government, Canning (age 70 years) led a new expedition to complete reconditioning of the northern wells to reopen the stock route which had been virtually abandoned. Subordinates remembered how he walked the whole distance twice: leading the men to a well, then while the men were cleaning it, walking on 24 km ahead to locate the next one. After this tremendous feat, he lived in retirement until he died of progressive muscular atrophy at his home in Perth on 22 May 1936. He was buried in Karrakatta cemetery with Church of England rites and left an estate that was valued for probate at £A1012.

Source, drawn from: Slee, John: Canning, Alfred Wernam (1860 - 1936), Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 7, Melbourne University Press, 1979, pp 557-558. (Obtained from web search on Alfred Wernam Canning, April 2009.)

References

1. Blackburn, Geoff: Calvert's Golden West, Hesperian Press, Victoria Park, 1997.

2. Bohemia, Jack and McGregor, Bill: Nyibayarri: Kimberley Tracker, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, 1995

3. Burbidge, Andrew A: et al, Aboriginal Knowledge of the Mammals of the Central Desert of Australia, in Australian Wildlife Resources, 1988, 15, pp 9-39. (Obtained from web search on Lanagan, April 2009 that yielded: http://www.publish.csiro.au/?act=view_file&file_id=WR9880009.pdf .)

4. Canning, AW: Plan of Wiluna-Kimberley Stock Route Exploration also shewing positions of wells constructed 1908-9-10, Memento map for the 150th Anniversary Celebrations of Western Australia, Department of Mines, Perth, 1978.

5. Carnegie, David W: Spinifex and Sand: A Narrative of Five Years Pioneering and Exploration in Western Australia, C Arthur Pearson Limited, London, 1898. (Downloaded during April- May 2009 from Journals of Australian Land and Sea Explorers and Discoverers; Project Gutenberg Australia e-books accessed at http://gutenberg.net.au/explorers-journals.html .)

6. Cannon, Michael: The Exploration of Australia, Readers Digest, Sydney, 1987.

7. Chudleigh, DC: Retracing the Canning Stock Route and Other Early Explorers' Routes in Central Western Australia, The Australian Surveyor, December 1969, pp 555-563.

8. Davenport, Sue; Johnson, Peter; and Yowali: Cleared Out: First Contact in the Western Desert, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, 2005.

9. Deasey, William Denison: Warburton, Peter Egerton (1813 - 1889), Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre for Biography, Australian National University. (Obtained from web search on Peter Egerton Warburton, May 2009 which yielded: http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/warburton-peter-egerton-4798/text7993 .)

10. Deckert, John: The Canning Stock Route 3rd Edition, Westprint Heritage Maps, Nhill, 2004.

11. Donaldson, Mike and Elliot Ian, Eds, Do Not Yield To Despair: Frank Hugh Hann's Exploration Diaries in the Arid Centre of Australia, Hesperian Press, Victoria Park, 1998.

12. Ford, RA: The Division of National Mapping's Part in the Geodetic Survey of Australia, The Australian Surveyor, June, September & December 1979, Vol 29, Nos 6-8.

13. Forrest, John: Explorations in Australia, Sampson Low, Marston, Low, & Searle, London, 1875. (Downloaded during April- May 2009 from Journals of Australian Land and Sea Explorers and Discoverers; Project Gutenberg Australia e-books accessed at http://gutenberg.net.au/explorers-journals.html .)

14. Giles, Ernest: Australia Twice Traversed: The Romance Of Exploration, Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington Limited, London, 1889. (Downloaded during April- May 2009 from Journals of Australian Land and Sea Explorers and Discoverers; Project Gutenberg Australia e-books accessed at http://gutenberg.net.au/explorers-journals.html .)

15. Hema Maps Pty Ltd: Australia's Great Desert Tracks (map series), North West Sheet, 4th Edition, 2007, Eight Mile Plains.

16. Hewitt, David: A Brief History of the Canning Stock Route, 29pp booklet prepared for Canning Stock Route Aerial Tours, East Victoria Park, (revised) 1980. Copy provided by the late David Roy Hocking circa 1984.

17. Gregory, Augustus Charles and Gregory, Francis Thomas: Journals of Australian Explorations, James C Beal, Government Printer, Brisbane, 1884. (Downloaded during April- May 2009 from Journals of Australian Land and Sea Explorers and Discoverers; Project Gutenberg Australia e-books accessed at http://gutenberg.net.au/explorers-journals.html .)

18. Johnson, HA: Geodetic Surveys through the Australian Sandridges, The Australian Surveyor, September 1964, pp157-184.

19. Kennedy, Brian and Barbara: Australian Place Names, Hodder and Stoughton, 1992, Sydney.

20. Macauley, Robert: Report on Blue Streak F2 Patrol October 1964, Patrol Report, 13 November 1964, National Archives of Australia, Canberra Office, A6456 R136/008. (Downloaded on 11 May 2009 from: http://mc2.vicnet.net.au/home/pmackett/RMacaulay_13_11_1964.html .)

21. Morrison, Doug: Geophysical History: 90 years ago some pioneering field trips (Part 1) A geophysicist and some camels, Preview, April 2005, No115 pp 16-19, Australian Society of Exploration Geophysicists, Perth. (Obtained from web search, April 2009 on Kidson which yielded: http://www.publish.csiro.au/?act=view_file&file_id=PVv2005n115.pdf .)

22. Readers Digest Services Pty Limited (Eds): Readers Digest Atlas of Australia, Readers Digest Services Pty Limited, Sydney, 1977, (in which the maps were sourced from the Division of National Mapping's 1:1million scale International Map of the World series).

23. Shire of Halls Creek: website, accessed April 2009.

24. Shire of Wiluna: website, accessed April 2009.

25. Slee, John: Canning, Alfred Wernam (1860 - 1936), Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre for Biography, Australian National University. (Obtained from web search on Alfred Wernam Canning, April 2009, which yielded: http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/canning-alfred-werman-5499/text9355 .)

26. Smith, Eleanor: The Beckoning West: the story of H. S. Trotman and the Canning Stock Route, Hesperian Press, Victoria Park, 1998 (first published 1966).

27. Steele, Christopher Wells, Lawrence Allen (1860 - 1938), Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre for Biography, Australian National University. (Obtained by web search May 2009 on http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/wells-lawrence-allen-9043/text15931 .)

28. Warburton, Peter Egerton: Journey Across The Western Interior Of Australia, Sampson Low, Marston, Low, & Searle, London, 1875. Facsimile edition, Hesperian Press, Victoria Park, 1981.

29. Waterson, DB: Gregory, Sir Augustus Charles (1819 - 1905), Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre for Biography, Australian National University. (Obtained from web search on AC Gregory in April 2009 that yielded: http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/gregory-sir-augustus-charles-3663/text5717 .)

30. Wells, LA: Journal of the Calvert Scientific Exploring Expedition, 1896-97, Wm Alfred Watson, Government Printer, Perth, 1902. Facsimile edition, Hesperian Press, Victoria Park, 1993.

31. Whittell, H M: Herman Franz Otto Lipfert, The Emu, Vol. XL, pp118-119, August 1940. (Obtained from web search on Canning in April 2009 that yielded:

www.publish.csiro.au/?act=view_file&file_id=MU940118.pdf .)

Prepared during April & May 2009.

Appendix A

Source: Canning, A W, Plan of Wiluna-Kimberley Stock Route Exploration also shewing positions of wells constructed 1908-9-10, Memento map for the 150th Anniversary Celebrations of Western Australia, Department of Mines, Perth, 1978.

Appendix B

CANNING STOCK ROUTE WATERS

LEAVING WILUNA

|

No |

Name |

No |

Name |

|

1 |

Well |

35 |

Minjoo, N slightly E is Bungabinni native well. |

|

2 |

Nigarra Well |

36 |

Wanda. NE of Wanda is Ural native well (n w). |

|

3 |

Well |

37 |

Libral |

|

4 |

North Pool |

38 |

Wardabunni |

|

5 |

Bore |

39 |

Murguga |

|

6 |

Lake Nabberu |

40 |

Waddawalla |

|

7 |

Soak |

41 |

Tiru. To the NE is Gunowarba native well. |

|

8 |

Windich Springs |

42 |

Guli. East and slightly north is Warrabuda n w |

|

9 |

Pierre Spring |

43 |

Billowaggi |

|

10 |

Bore |

44 |

Well |

|

11 |

Weld Spring |

45 |

Well |

|

12 |

Goodwin Soak |

46 |

Kuduarra |

|

13 |

Soak |

47 |

Well |

|

14 |

Native Well |

48 |

Well. Between 47 and 48 a bore was sunk. |

|

15 |

Well |

49 |

Well |

|

16 |

Bore |

50 |

Well |

|

17 |

Killagurra. Slightly to the NE is Durba Springs |

51 |

Weriaddo |

|

18 |

Well. To the NE is Onegunyah Rockhole |

52 |

Guda Soak to NE of Weriaddo, Gregory's Salt Sea on the E. |

|

19 |

Kunanaggi, with Lake Disappointment on the E |

53 |

Billiluna Pool |

|

20 |

Well |

54 |

Kura Soak. Permanent water, slightly brackish. |

|

21 |

Well due W is Gunanya Spring in McKay Range. |

55 |

Wolfe Creek |

|

22 |

Well. Sunk on a rockhole. |

56 |

Ima Ima Pool |

|

23 |

Well, with native water to the E |

57 |

Wowaljarrow Pool |

|

24 |

Karrara Soak |

58 |

Waterhole |

|

25 |

Well |

59 |

Buee Pool |

|

26 |

Well |

60 |

Waterhole |

|

27 |

Well. Situated close by a native water. |

61 |

Chuall Pool |

|

28 |

Well. Due N of it is another native well. |

62 |

Bindi Bindi Waterhole |

|

29 |

Well. Thring Rock to the NW of it. |

63 |

Ten Mile Creek |

|

30 |

Dundajinnda. Nangabittajarra is SW. |

64 |

Anjammie Pool |

|

31 |

Well. |

65 |

Waterholes |

|

32 |

Mallowa |

66 |

Cow Creek |

|

33 |

Gunowaggi |

67 |

Flora Valley Station |

|

34 |

Nibil |

68 |

Hall's Creek |

Notes: Well 31-To the E slightly S is Wullowla. SW of Wullowla is Nurguga; slightly N and E of Dundajinnda is Mujingerra, all native waters. Well 37-NE of Libral is Billigilli native well and NW of that is Wandurba Rockhole. Well 44-S of well is Burnagu sand soak. N and slightly W of Well 44 is Jimberingga native well, NW of which is Pijallinga claypan. Well 49-Lumba is slightly SW of Well 49. Between Well 48 and Well 49 are Kunningarra Rockhole and Godfrey's Tank, both very close together and NE of Well 48.

The above is a list of the native waters, bores and wells sunk by Canning's party during 1908-10. The list is from Canning's field notes but has been slightly modified to fit the above table format, eg cardinal points given as N rather than north etc and lengthier notes put below rather than in table.

Source: Smith, Eleanor, The Beckoning West: the story of H. S. Trotman and the Canning Stock Route, Hesperian Press, Victoria Park, 1998 (first published 1966), pp209-211.

Appendix C

Source: Smith, Eleanor, The Beckoning West: the story of H. S. Trotman and the Canning Stock Route, Hesperian Press, Victoria Park, 1998 (first published 1966), facing p 85.

Appendix D

Kidson Expedition at Well 37 on 18 July 1914. (CIW/DTM-GL Library photo #4170)

Kidson Expedition at Wiluna circa 14 June 1914. (CIW/DTM-GL Library photo #4154)

Source: Morrison, Doug, Geophysical History: 90 years ago some pioneering field trips (Part 1) A geophysicist and some camels, Preview, April 2005, No115 pp 16-19, Australian Society of Exploration Geophysicists, Perth. Obtained from web search, April 2009 on Kidson which yielded: http://www.publish.csiro.au/?act=view_file&file_id=PVv2005n115.pdf

Appendix D (continued)

Kidson Expedition at Lake Tobin (between Wells 39&40) circa 20 July 1914. (CIW/DTM-GL Library photo #4173)

Edward Kidson O B E (Mil), M Sc M A, D Sc, Elnst P, FRSNZ

(1882 - 1939)

Source: Morrison, Doug, Geophysical History: 90 years ago some pioneering field trips (Part 1) A geophysicist and some camels, Preview, April 2005, No115 pp 16-19, Australian Society of Exploration Geophysicists, Perth. Obtained from web search, April 2009 on Kidson which yielded: http://www.publish.csiro.au/?act=view_file&file_id=PVv2005n115.pdf

Appendix E

Locke Oil Expedition1922. (Battye 003834d)

![Description: 003835d[1]](csr%20nu_files/image010.jpg)

Locke Oil Expedition 1922. (Battye 003835d)

Source: J S Battye Library of West Australian History: www.liswa.wa.gov.au/wepon/mining/html/003834d.html and www.liswa.wa.gov.au/wepon/mining/html/003835d, accessed by web search for Locke Oil Expedition 1922 in May 2009.

Appendix F

The Early European Explorers who travelled over parts of the Canning Stock Route

The purpose of this appendix is to allow the reader to gain an appreciation of the early European explorers' own words on their coming to grips with the country through which the stock route would later traverse. As can be gleaned from the following, it was and remains a harsh and unforgiving environment. The reader may also glean that, judged by contemporary standards, the explorers' attitudes towards and treatment of the traditional Aboriginal owners of this land was no less harsh. Brief biographical details of each explorer are included in each section.

Edited breaks in the explorers' original text have been made and noted. These were made for reasons of economy of space for this appendix; as were changes to fonts and formats. Highlights have been made to the original texts where important features, positions or dates are mentioned. Annotations have also been added where the explorers' travels coincide with the line of the future stock route.

Contents

|

Augustus Charles Gregory explored the northern part of the stock route in 1856 naming Sturt Creek and discovering what is now called Lake Gregory (Well 51 is now nearby and Canning's route followed Sturt Creek much of the way from there to Halls Creek). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Peter Egerton Warburton crossed the northern part of the stock route in 1873 at Mount Romilly and passed near Well 47. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

John Forrest found and named waters on the southern section of the stock route in 1874 that Canning later used, namely Windich Springs (No 4A Water), Pierre Spring (Well 6) and Weld Springs (Well 9). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ernest Giles crossed the stock route in 1876 between the Calvert Range and Trainor Hills to the north of Well 15. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lawrence Wells travelled to the east of the stock route in 1896 naming the Runton Range, Calvert Range and Trainor Hills (near Wells 15 and 16) and later that year crossed the stock route between Wells 29 and 30, naming Thring Rock, King Hill and Lake Auld. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

David Carnegie's expedition from the southern goldfields to Halls Creek in 1896 touched on the northern part of the stock route around Wells 48 and 49, he named many features including the Southesk Tablelands, Godfrey's Tank, Breaden Pool Twin Heads and Mount Ernest. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Frank Hann discovered and named Lake Disappointment and the Mackay and McFadden Ranges his route came near Wells 19 and 20. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Augustus Charles Gregory 1819 - 1905

(Photo Source: National Library of Australia. nla.pic-an10791281-2.)

![Description: Sir Augustus Charles Gregory [picture].](csr%20nu_files/image011.jpg)

Gregory was born on 1 August 1819 at Nottinghamshire, England, the second of five sons of Joshua Gregory and his wife Frances, née Churchman. His father accepted a land grant in the new Swan River settlement in 1829. Aided by neighbour, Surveyor-General John Roe, Augustus became a cadet in his department in 1841 and was soon promoted an assistant surveyor. He worked mainly in the country, marking out roads and town sites and issuing pastoral licences, often with his brothers as his chainmen. He also Gregory was born on 1 August 1819 at Nottinghamshire, England, the second of five sons of Joshua designed an apparatus to operate the first revolving light installed on Rottnest Island.

Gregory's resource, bushcraft, facility for invention and technical expertise won him the confidence of his superiors and in 1846 he was given command of his first expedition. In seven weeks with his brothers Francis and Henry Churchman he travelled north of Perth, and returned in December to report good grazing land and a promising coal seam on the Irwin River. A group of colonists invited him in 1848 to lead a settlers' expedition to map the Gascoigne River and seek more pastoral land. The party charted part of the Murchison River and found traces of lead which led to the opening of the Champion Bay district centred on Geraldton. Gregory continued to mark out roads and stockroutes and look for grazing land and minerals until 1854 when the imperial government decided to sponsor a scientific exploration across the north of Australia and Gregory was chosen to lead it. With eighteen men, including his brother Henry, Ferdinand von Mueller and other scientists he sailed from Moreton Bay in August 1855 and in September reached the estuary of the Victoria River. After initial set-backs Gregory led several forays up the Victoria River and traced Sturt's Creek for 480 km until it disappeared in desert. Turning east the party explored the Elsey, Roper and Macarthur Rivers, crossed and named the Leichhardt and then travelled to Brisbane by way of the Flinders, Burdekin, Fitzroy and Burnett Rivers. In sixteen months the expedition had journeyed over 3200 km by sea and 8000 km by land. The natural resources discovered did not measure up to expectations but Gregory was awarded the gold medal of the Royal Geographical Society and his report later stimulated much pastoral settlement. Although Gregory attributed his success to 'the protection of that Providence without which we are powerless', the smooth passage and thorough scientific investigations of the expedition owed much to his leadership. Paradoxically it was too successful to be recognized as one of the most significant journeys led by one of the few unquestionably great Australian explorers. Modest, unromantic and resolute in following instructions, he did not dramatize his report, boasted no triumphs and sought no honours despite his admirable Aboriginal policy and meticulous organization. He excelled as a surveyor and manager of men, horses and equipment, and invented improvements for pack-saddles and pocket compasses. His seasonal knowledge and bushcraft were unparalleled and he was the first to note the sequence of weather patterns in Australia from west to east. Gregory's qualities were again displayed in 1858 when he led an expedition for the New South Wales government in search of Ludwig Leichhardt. From Juandah station he went west, crossed the Warrego and Barcoo Rivers but after finding traces of the lost explorer was forced by drought to abandon the search and travel south to Adelaide. This was his last major expedition. He marked the southern boundary of Queensland and in 1859 became its first commissioner for crown lands and surveyor-general. He relinquished lands in 1863, on 12 March 1875 became geological surveyor.

Gregory had the most onerous duties in the new government for land was the colony's greatest resource. He was responsible for classifying and controlling an area of 1,700,000 km² inhabited by only 12,000 people with differing concepts of land alienation and use. Although he worked with speed and efficiency, his 'qualities as an explorer were not matched by his ability to institute and oversee a large, complicated and important Government department'. He had little patience for administrative process but relied on a combination of practical experience, technical skill and a network of intimates which included squatters, bushmen, explorers and surveyors. Gregory was appointed to the Legislative Council on 10 November 1882. Always a critic of the government, he opposed all radical legislation and social reform and allied himself with the most reactionary squatting group in the House. In local government at Toowong he served as president of the divisional board and in 1902 became first mayor. For his public services he was made C.M.G. in 1874 and K.C.M.G. in 1903 for his contribution to Australian exploration. He died unmarried at Rainworth, his Brisbane home, on 25 June 1905 and was buried in Toowong cemetery.

Extract only from:

JOURNALS OF AUSTRALIAN EXPLORATIONS

BY

AUGUSTUS CHARLES GREGORY,

C.M.G., F.R.G.S., ETC.,

Gold Medalist, Royal Geographical Society,

AND

FRANCIS THOMAS GREGORY,

F.R.G.S., ETC., ETC.,

Gold Medalist, Royal Geographical Society.

BRISBANE:

JAMES C. BEAL, GOVERNMENT PRINTER, WILLIAM STREET.

1884.

ENTER WESTERN AUSTRALIA 21st February 1856 As we were now three days' journey from the last water which could be depended on for more than a few days, and the channel of the creek had been so completely lost on the plain that it was uncertain whether the marks of inundations near this camp had been caused by the creek flowing to the west, or by some tributary flowing to the east, I determined to attempt a south-west course, in the hope that, should the country prove rocky, the heavy showers might have collected a sufficient quantity of water to enable us to continue a southerly route, and accordingly selected the most prominent point of the rising ground to the south of our position, and at 6.5 a.m. started north 235 degrees east. After leaving the open plains we entered a grassy box forest, which continued to the foot of the hills, which we reached at 8.0. The slope of the hills proved very scrubby, with small eucalypti and acacia, the soil red sand and ironstone gravel; at 9.0 reached the highest part of the hills for many miles round. To the south the country was slightly depressed for ten or fifteen miles, and then rose into an even ridge or plain, the whole country appearing to be covered with acacia and eucalyptus scrub. To the west and north the view was more extended; the low ridge of sandstone hills extended to the west-north-west, on the northern side of the grassy flats for thirty miles, and only broken by a large valley from the north. Throughout its whole extent this range appeared to rise to 150 or 200 feet above the plain, and had the appearance of being the edge of a level tableland. South of the grassy plain, the western limit of which was not seen, the country rose gradually to eighty or 100 feet, and presented an extremely level and unvaried appearance. It was evident that our only chance of farther progress was to follow the grassy plain to the west till some change in the country rendered a southerly course practicable, it being probable that some creek from the north might join the grassy plain, and that the channel which had been lost might be reformed. At 9.30 steered north-west, and at 12.30 p.m. cleared the acacia scrub, and at 1.30 reached the bank of the creek, which had formed a channel twenty yards wide, with pools of water, which was brackish; but we were too glad to find any water which we could use without detriment to object to it because it was not agreeable in taste, and therefore encamped. We have thus been a second time compelled to make a retrograde movement to the north after reaching the same latitude as in the first attempt to penetrate the desert; but I did not feel justified in incurring the extreme risk which would have attended any other course, though following the creek is by no means free from danger, as very few of the waterholes which have supplied us on the outward track will retain any water till the time of our return. The weather was calm and hot in the early part of the day, and in the afternoon it clouded over, and there was a slight shower of rain. According to our longitude, by account, we have this day passed the boundary of Western Australia, which is in the 129th meridian. Latitude by Canopus and Procyon 18 degrees 26 minutes.

STURT'S CREEK 22nd February. Leaving the camp at 5.40 a.m., followed the creek to the west-south-west and crossed a small gully from the south; at 11.30 a.m. camped at a fine pool of water in a small creek from the south, close to its junction with the principal creek, which we named after Captain Sturt, whose researches in Australia are too well known to need comment; the grassy plains extended from three to ten miles on each side of the creek, which has a more definite channel than higher up, there being some pools of sufficient size to retain water throughout the year; the plain is bounded on the north by sandstone hills 100 to 200 feet high, and there is also a mass of hilly country to the south, the highest point of which was named Mount Wittenoon; about noon a thunder-shower passed to the east and up the creek on which we were encamped, and though the channel was then dry between the pools, at 4.0 p.m. it was running two feet deep; the grass is much greener near this camp, and there has evidently been more rain here than in any part of the country south of Victoria yet visited; a fresh southerly breeze in the morning, thunderstorms at noon, night cloudy with heavy dew.

Canning's Well 51 Weriaddo lies south west of Lake Gregory and his route followed Sturt Creek much of the way from there to Halls Creek. With its old homestead situated on Sturt Creek at the northern end of Lake Gregory, Billiluna Station of some 160,000 hectares was first taken up in 1920 and became the main user of the Canning Stock Route.

23rd February At 5.50 a.m. resumed our journey down the creek, the general course first south-west and changing to the south-south-west; the channel was gradually lost on the broad swampy flat, which was overgrown with polygonum and atriplex, etc., and had a breadth of half a mile to a mile, being depressed about ten feet below the grassy plain; the grassy plain also extended to about fifteen miles wide, the hills decrease in height, and the whole country is so level that little is to be seen but the distant horizon, scarcely in any part rising above the vast expanse of waving grass. At 10.50 a.m. camped at a shallow puddle of muddy water, just sufficient to supply the horses; I walked about a mile into the polygonum flat, but could not find any water, though the ground was soft and muddy in a few spots. Mr. H.C. Gregory, when rounding up the horses in the evening, saw eight blacks watching us; we therefore went out to communicate with them; but they hid themselves in the high bushes and grass. The night was clear, and I took a set of lunar distances, which the cloudy weather had prevented for more than a week, though I had been able to get altitudes for latitude. Latitude by Canopus, Castor and Pollux 18 degrees 39 minutes 54 seconds.

EFFECT OF SEASONS ON APPEARANCE OF COUNTRY. 24th February. At 6.0 a.m. resumed our journey down the creek, which spread into a broad swampy flat about a mile wide, and covered with atriplex, polygonum, and grass, the general trend south-west; at 7.30 crossed a large watercourse from the south-east, with a dry sandy channel, no water having flowed down it this season; at 9.0 a.m. crossed to the right bank of the creek; there were many shallow muddy channels and one with running water four yards wide and one foot deep; the largest channel was near the right bank, but, except a large shallow pool, it was dry. As we advanced the country showed effects of long-continued drought, and though the creek contained some large shallow pools, the channel was dry between, the dry soil absorbing the whole of the water which was running in the channel above; at 11.50 camped at what appeared to be the termination of the pools of water, as the channel was again lost in a perfectly level flat. Great numbers of ducks, cockatoos, cranes, and crows frequented the banks of the creek above the camp, and appeared to feed on the wild rice which was growing in considerable quantities in the moist hollows, as also a species of panicum; to the south-east of the creek there is a level box-flat which extends two to three miles back to the foot of some low sandy ridges covered with triodia and a few small eucalypti; to the north-west and west the grassy plain extended to the horizon, with scarcely even a bush to intercept the even surface of the waving grass. Latitude by Canopus and Pollux 18 degrees 45 minutes 45 seconds.

25th February. The small number of water-fowl which passed up or down the creek during the night indicated that water was not abundant below our present position, and we were therefore prepared for a dry country, in which we were not disappointed, for leaving the camp at 6.15 a.m. we traversed a level box-flat covered with long dry grass; at 9.10 a.m. again entered the usual channel of the creek, which was now a wide flat of deeply cracked mud with a great quantity of atriplex growing on it, but which had lost all the leaves from the long continuance of the dry weather. The flat was traversed by numerous small channels from one to two feet deep, but they were all perfectly dry and had not contained water for more than a year; there were, however, marks of inundations in previous years, when the country must have exhibited a very different appearance, and had it been then visited by an explorer, the account of a fine river nearly a mile wide flowing through splendid plains of high grass, could be scarcely reconciled with the facts I have to record of a mud flat deeply fissured by the scorching rays of a tropical sun, the absence of water, and even scarcity of grass. The creek now turned to the south, and we followed the shallow channels till 12.30 p.m., when we fortunately came to a small pool which had been filled by a passing thunder-shower, and here we encamped during the day; a fresh breeze at times blew from the south-east and south, and the air was exceedingly warm; thermometer 106 degrees at noon, but being very dry, was not very oppressive. Latitude by Canopus, Castor and Pollux 18 degrees 55 minutes 45 seconds.

LEVEL COUNTRY 26th February. As the course of the creek was uncertain, we steered south at 5.45 a.m. across the atriplex plain, and at 6.35 reached the ordinary right bank of the creek, which was low and gravelly, covered with triodia and small bushes; we then passed a patch of white-gum forest, and at 8 entered a grassy plain which had been favoured by a passing shower; green grass was abundant, and even some small puddles of water still remained in the hollows of the clay soil. At 10.50 came on the creek, which had collected into a single channel and formed pools, some of which appeared to be permanent, as they contained small fish. At one of these pools we encamped at 11.10. The channel of the creek is about fifteen feet below the level of the plain, and is marked by a line of small flooded-gum trees, the atriplex flat has ceased, and the soil is a hard white clay, producing salsola and a little grass; the morning clear with a moderate easterly breeze, afternoon cloudy with a few drops of rain at night. Latitude by Canopus and Pollux 19 degrees 7 minutes 30 seconds.

27th February. Resumed our journey down the creek at 6.5 a.m., when it turned to the west and formed a fine lake-like reach 200 yards wide, with rocky banks and sandstone ridges on both sides of the creek; at 11.0 camped at the lower end of a fine reach trending south: the general character of these reaches of water is that they are very shallow and are separated by wide spans of dry channel, the water being ten feet below the running level. The country is very inferior, and the grassy flats are reduced to very narrow limits, and the hills are red sandstone, producing nothing but small trees and triodia. Latitude by Canopus and Pollux 19 degrees 12 minutes 20 seconds.

28th February. At 6.0 a.m. we were again in the saddle, following a creek which had an average west-south-west course, but the channel was soon lost in a wide grassy flat, with polygonum and atriplex, in this flat were some large detached pools of water, 50 to 100 yards wide and a quarter to half a mile long, although the dry season had reduced them to much narrower limits than usual, as they were now eight to ten feet below the level of the plain; at 11.45 camped at a large sheet of water, just above a remarkable ridge of sandstone rocks on the right bank of the creek. Ducks, pelicans, spoonbills, etc., were very numerous, but so wild that they could scarcely be approached within range of our guns; until the present time it has been doubtful whether the creek turned towards Cambridge Gulf, the interior, or to the coast westward of the Fitzroy, but the first point being now 220 nautic miles to the north, and the general course of Sturt's Creek south-west, such a course is not probable, and it therefore only remains to determine whether it is lost in the level plains of the interior, or finds an outlet on the north-west coast. The careful and minute surveys of the coast from the Victoria River to Roebuck Bay show that no rivers exist of such magnitude as the Sturt would attain in passing through the ranges to the coast, nor does the general abrupt character of the coast-line favour the supposition that any interior waters would find an outlet in this space. That the elevation of this part of the creek is sufficient to enable it to form a channel to the north-west coast is shown by the barometric measurement: the dividing ridge between the head of the Victoria and Hooker's Creek is about 1200 feet, at the head of Sturt's Creek 1,370 feet, and our present camp 1100 feet; thus the average fall of Sturt's Creek has been 270 feet in 180 miles, or one and a half feet per mile. Now the distance to Desault Bay (which appears the most probable outlet) is 370 miles, and allowing an increase of 500 for deviations, there would be more than two feet descent per mile, which would be sufficient for the maintenance of a channel. Should the creek turn to the south and enter the sandy desert country, the water would soon be absorbed, especially as the wet season at the upper part of the creek occurs when the dry season is prevailing in the lower part of its course. That it does lose itself in a barren sandy country is, I fear, the most probable termination of the creek, and that a level country exists for many miles on each side of our route is shown by the small number and size of the tributary watercourses. Latitude by Canopus, Castor and Pollux 19 degrees 18 minutes 10 seconds.

29th February. Leaving the camp at 5.40 a.m., traced the creek to the south-west for about three miles. It formed fine reaches of water fifty to 100 yards wide; but the channel terminated suddenly in a level flat, covered with polygonum, atriplex, and grass. In this flat we passed some large shallow pools of water; at 7.30 the creek turned to the west round the north end of a rocky sandstone hill, and was joined by a tributary gully from the north, below which point the channel was a well-defined sandy bed, with long parallel waterholes on each side, but very little water remained at this time; at 9.15 the course of the creek changed to south by west, and passed through a level flat timbered with flooded-gum trees; it was about one mile wide and well grassed, but completely dried up for want of rain. The back country was thinly wooded with white-gum, and gently rising as it receded, forming sandstone hills about 100 feet high of extremely barren appearance; at 11.45 camped at a small muddy pool which would last only for a few days. A strong breeze from the west commenced early in the day, and gradually changed to the south. Thermometer, 109 degrees in the coolest shade that could be found. Latitude by Canopus and e Argus 19 degrees 28 minutes 5 seconds.

DESERT OF RED SAND 1st March. Our horses having strayed farther than usual in search of better grass, we were delayed till 6.20 a.m., when we steered a south by west course down the valley of the creek. Immediately below the camp the country beyond the effect of inundation changed to a nearly level plain of red sand, producing nothing but triodia and stunted bushes. The level of this desert country was only broken by low ridges of drifted sand. They were parallel and perfectly straight, with a direction nearly east and west. At 11.50 camped at a fine pool of water three to five feet deep and twenty yards wide. That we had actually entered the desert was apparent, and the increase of temperature during the past three days was easily explained; but whether this desert is part of that visited by Captain Sturt, or an isolated patch, has yet to be ascertained, and the only hope is that the creek will enable us to continue our course, as the nature of the country renders an advance quite impracticable unless by following watercourses. Latitude by Canopus, Castor and Pollux 19 degrees 40 minutes 45 seconds.

2nd March. Left our camp at 6.30 a.m., and steered south-west by west, which soon took us into the sandy desert on the left bank of the creek. Crossing one of the sand ridges, got a sight of a range of low sandstone hills to the south-east, the highest of which I named Mount Mueller, as the doctor had seen them the previous evening while collecting plants on one of the sandy ridges near the camp. At 10.15 again made the creek, which had scarcely any channel to mark its course; the wide clay flat bearing marks of former inundations was the only indication visible. At 12.35 p.m. camped at a small muddy pool, the grass very scanty and dry. Traces of natives are frequent. Large flights of pigeons feed on the plains on the seeds of grass. A flock of cockatoos was also seen. Latitude by Canopus and Pollux 19 degrees 51 seconds 12 minutes.

3rd March. At 5.30 a.m. started and followed the creek on a general course south-west. There was a very irregular channel sometimes ten yards wide and very shallow, and then expanding into pools fifty yards wide. The sandy plain encroached much on the grassy flats, and reduced the winter course of the creek to half a mile in breadth. At 8.0 the course was changed to south, and at 10.15 camped at a swamp, which was nearly dry, and covered with beautiful grass. The country differed in character from that seen yesterday, there being a few scattered white-gum trees and patches of tall acacia. Salsola and salicornia are also very abundant, and show the saline nature of the soil. Latitude by Canopus and Pollux 20 degrees 2 minutes 10 seconds.

SALT LAKES 4th March. Left the camp at 5.50 a.m., and steered south-west over a very level country, with shallow hollows filled with a dense growth of acacia, and at 7.30 struck the creek with a sandy channel and narrow flats, covered with salsola and salicornia. The pools were very shallow, and gradually became salt, and at 10.15 it spread into the dry bed of a salt lake more than a mile in diameter. This was connected by a broad channel with a pool of salt-water in it, with a second dry salt lake eight miles in diameter. As there was little prospect of water ahead and the day far advanced, we returned to one of the brackish pools and encamped. The country passed was of a worthless character, and so much impregnated with salt that the surface of the ground is often covered with a thin crust of salt. Latitude by e Argus 20 degrees 10 minutes 40 seconds.

5th March. Started from the camp at 5.45 a.m., and steered south-south-east through the acacia wood to the lake, and then south by east across the dry bed of the lake towards a break in the trees on the southern side. Here we found a creek joining the lake from the south-west, in which there were some shallow pools. We then steered east, to intersect any channel by which the waters of the lake might flow to the south or south-east, and passing through a wood of acacia entered the sandy desert. As some low rocky hills were visible to the east we steered for them. At 2.10 halted half a mile from the hills, and then ascended them on foot. They were very barren and rocky, scarcely eighty feet above the plain, formed of sandstone, the strata horizontal. From the summit of the hill nothing was visible but one unbounded waste of sandy ridges and low rocky hillocks, which lay to the south-east of the hill. All was one impenetrable desert, as the flat and sandy surface, which could absorb the waters of the creek, was not likely to originate watercourses. Descending the hill, which I named Mount Wilson, after the geologist attached to the expedition, we returned towards the creek at the south end of the lake, reaching it at 9.30.

6th March. As the day was extremely hot and the horses required rest and food, we remained at the camp. Ducks were numerous in some of the pools, but so wild that only two were shot. The early part of the day was clear, with a hot strong breeze varying from west to south-east. At 1 p.m. there was a heavy thunder-squall from the south-east, which swept a cloud of salt and sand from the dry surface of the lake. The squall was followed by a slight shower. Latitude by Canopus 20 degrees 16 minutes 22 seconds.

DRY BEDS OF SALT LAKES 7th March. As I had frequently observed that in the dry channels of creeks traversing very level country a heavy shower in the lower part of its course often causes a strong current of water to rush up the stream-bed and leave flood marks, which would mislead a person examining them in the dry season, it seemed probable that this must be the case with the creek entering the salt lake at its south-west angle, as it might be the outlet of the lake when filled by Sturt's Creek flowing into it, though in ordinary seasons the flow of water would be into the lake; accordingly I decided on following the creek and ascertain its actual course. Leaving the camp at 5.50 a.m., steered nearly south-west along the general course of the creek till 7.30, when it turned to the north and entered the dry bed of a lake. As the beds of the two lakes were lower than the channel between them, the water during the last heavy rains had flooded both ways from the central part of the channel. Having skirted the lake on the west to intercept any watercourses which might enter or leave the lake on that side, we came to a large shallow channel with pools of water--some fresh and others salt--with broad margin of salicornia growing on the banks; at 11.0 camped at a small pool of fresh water. The soil of the country on the bank of the creek is loose white sand with concretions of lime, covered with a dense growth of tall acacia, with salsola and a little grass in the open spaces.

TERMINATION OF STURT'S CREEK 8th March Started at 6.5 a.m. and traced the creek into a salt lake to the west, but this was also dry. After some search we found a creek joining on the northern side and communicating with a large mud plain, partly overgrown with salicornia, and with large shallow pools of muddy water two to three inches deep. On the northern side the plain narrowed into a sandy creek with shallow pools, the flow of the water being decidedly from the northward. At 12.15 p.m. camped at a shallow pool, near which there was a little grass, the country generally being sandy and only producing triodia and acacia. Thus, after having followed Sturt's Creek for nearly 300 miles, we have been disappointed in our hope that it would lead to some important outlet to the waters of the Australian interior; it has, however, enabled us to penetrate far into the level tract of country which may be termed the Great Australian Desert. Latitude by Pollux and e Argus 20 degrees 4 minutes 5 seconds. (While Gregory did not name the salt lake, it later known as Gregory's Salt Sea but is now known as Lake Gregory.)

9th March. Left our camp at 6.35 a.m., and followed the creek up for half an hour, and then steered east to Sturt's Creek, which we reached at 9.5, the country being level, sandy, and covered with triodia and acacia in small patches; we then steered a southerly course down the creek till 11.0, and camped at the large brackish pool.

(COMMENCE RETURN TO DEPOT)

Source for above text: downloaded during April- May 2009 from Journals of Australian Land and Sea Explorers and Discoverer; Project Gutenberg Australia e-books accessed at http://gutenberg.net.au/explorers-journals.html. (To fit economically into this document some minor format and font changes have been made.) Source for above biographical article: Waterson, DB, Gregory, Sir Augustus Charles (1819 - 1905), Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 4, Melbourne University Press

Peter Egerton Warburton (1813-1889

Peter Egerton Warburton was born on 16 August 1813 at Northwich in Cheshire, England. He entered the navy at 12 and served as midshipman in the Windsor Castle. Between 1829 and 1831 he was at the Royal Indian Military College, Addiscombe before joining the 13th Native Infantry Battalion, Bombay Army. He served until 1853and retired as assistant adjutant-general with the rank of major. On 8 October 1838 he had married Alicia Mant of Bath. In 1853 Warburton visited his brother George at Albany, Western Australia, before going to Adelaide where he became commissioner of police on 8 December. In 1857 he visited the area of Lake Gairdner and the Gawler Ranges and in 1858 the government sent him north to recall and supersede BH Babbage's exploring party. Warburton continued with a companion towards Mount Serle, finding a way through Lake Eyre and South Lake Torrens. He discovered groups of springs, grazing land and the ranges he named after Sir Samuel Davenport. While the government disapproved of Warburton's criticism of Babbage, it praised his skill and granted him £100 for his achievements. Next year, however, £100 per annum was taken off his salary, and he continued to receive this reduced rate.

In 1860 with three mounted police he explored north-west of Streaky Bay; he covered about 320 km of barren country and reported unfavourably on it. In November 1864 Warburton was defeated by inhospitable country north-west of Mount Margaret and in 1866 he examined the area around the northern shores of Lake Eyre. He searched unsuccessfully for Sturt's Cooper's Creek, but found a large river, since named after him, which he traced to near the Queensland border. He returned in October.

After a secret court of inquiry into the police force, the government suggested that other employment more congenial to his habits and tastes should be found for Warburton, but refused to show him the evidence. He declined to resign and was dismissed early in 1867. A subsequent Legislative Council select committee on the police force failed to reveal why Warburton had been victimized, deplored his unfair treatment and vainly recommended reinstatement. On 24 March 1869 he accepted the lower salary of chief staff officer and colonel of the Volunteer Military Force of South Australia.

In 1872 Warburton left South Australia as leader of an expedition that included his son Richard and J. Lewis. It was financed and provided with seventeen camels and six months supplies by Sir Walter Hughes and Sir Thomas Elder. The expedition sought to link the province with Western Australia. After leaving Alice Springs in April 1873, they endured long periods of extreme heat with little water, and survived only by killing the camels for meat. They reached the Oakover River with Warburton strapped to a camel. On 11 January 1874 they were brought to Degrey Station in northern Western Australia. They had conquered the formidable Great Sandy Desert to become the first to cross the continent from the centre to the west. Warburton was emaciated and blind in one eye. At a public banquet in Adelaide later he attributed their survival to his Aboriginal companion Charley.